State of Student Aid in Texas – 2020

Section 13: Texas Higher Education and Student Debt Policy

- By 2030, at least 60 percent of Texans ages 25-34 will have a postsecondary credential or degree.

- By 2030, at least 550,000 students in that year will complete a certificate, associate, bachelor’s, or master’s degree from a Texas public, independent, or for-profit college or university.

- By 2030, all graduates from Texas public institutions of higher education will have completed programs with identified marketable skills.

- By 2030, undergraduate student loan debt will not exceed 60 percent of first-year wage for graduates of Texas public institutions.

In focusing on student debt and workforce outcomes, goals three and four represented a new direction for the THECB. The plan identified two key targets for containing student loan debt:

- Decrease the excess semester credit hours (SCH) that students attempt when completing an associate or bachelor’s degree to 12 by 2020, six by 2025, and three by 2030.

- Limit the need to borrow so that no more than half of all students who earn an undergraduate degree or certificate will have debt in 2030.

60x30TX Goal Updates

| 2015 (Baseline) | 2018 | 2030 Goal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Attainment Rate | 40.3% | 43.5% | 60% | |

| Completion Goals | Overall Completion Total | 311,340 | 341,307 | 550,000 |

| Hispanic Completion | 96,657 | 115,735 | 285,000 | |

| African American Completion | 38,964 | 41,594 | 76,000 | |

| Male Completion | 131,037 | 143,981 | 275,000 | |

| Economically Disadvantaged Completion | 114,176 | 124,471 | 246,000 | |

| Texas High School Graduates Enrolling in Texas Higher Education | 52.7% | 51.6% | 65% | |

| Marketable Skills Goal | Working or Enrolled Within One Year | 78.9% | 78.5% | 80% |

| Student Debt Goals | Student Loan Debt to First-Year-Wage Percentage | 59.5% | 59% | 60% |

| Excess SCH Attempted | 19 | 16 | 3 | |

| Percent of Undergraduates Completing with Debt | 49.2% | 45.8% | 50% |

Sources: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. THECB 60×30 Progress Report, July 2019 (http://www.60x30tx.com/media/1518/2019-60x30tx-progress-report.pdf).

HB 3: Relating to Public School Finance and Public Education

- Requires that high school students complete and submit a Federal Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or a Texas Application for State Financial Aid (TASFA) prior to graduation

HB 2140: Relating to Creating an Electronic Application System for State Student Financial Assistance

- Requires the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board to develop a process that would allow students to complete the Texas Application for State Financial Aid online on the same website as the common admission application form

HB 3808: Relating to Measures to Facilitate the Timely Graduation of and Attainment of Marketable Skills by Students in Public Higher Education

- Requires specified changes to the Texas College Work-Study Program, the Texas WORKS Internship Program, and the filing of a degree plan to aid in timely graduation and acquiring marketable skills

- Requires that public institutions designate a liaison officer for current and incoming students to provide them with comprehensive information about support services and other available resources

HB 2784: Relating to the Creation of the Texas Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Programs Grant Program

- Requires the Texas Workforce Commission to create and administer a program to encourage the private sector to develop apprenticeship programs

- No funding was appropriated with this bill

Sources: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB), Legislative and Media Resources, Higher Education Policy and Appropriations, “Summary of Higher Education Legislation, 86th Texas Legislature” (2019) (http://reportcenter.thecb.state.tx.us/training-materials/presentations/board-legislation-2019-summary/).

Major Texas Financial Aid Programs

Appropriated Funds by State Program and State Fiscal Year*

| State Fiscal Year 2019 | State Fiscal Year 2020 | State Fiscal Year 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Towards EXcellence Access and Success (TEXAS) Grant | $393.2 | $433.2 | $433.2 |

| Texas Educational Opportunity Grant (TEOG) | $47.9 | $47.9 | $47.9 |

| Texas College Work-Study | $9.4 | $9.4 | $9.4 |

| Tuition Equalization Grant (TEG) | $85.9 | $89.3 | $89.3 |

| B-on-Time Loan | $3.8 | $1.2 | $0 |

Other programs were appropriated level funding except for the B-on-Time Loan Program, which was repealed in 2015. The legislature has appropriated about $1.2 million for renewal awards for continuing students in state fiscal year 2020 and has not appropriated any funds for state fiscal year 2021.

All state grant programs assist students with financial need, promoting access to higher education to low-income students while helping to limit their need to borrow student loans, though some programs (like the TEXAS Grant) also have an explicit merit-based component.

Other Large Texas Financial Aid Programs

Appropriated Funds by State Program and State Fiscal Year*

| State Fiscal Year 2019 | State Fiscal Year 2020 | State Fiscal Year 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental Education | $1.3 | $1.3 | $1.3 |

| Texas Research Incentive Program | $17.5 | $17.5 | $17.5 |

| Professional Nursing Shortage Reduction Program | $9.9 | $9.9 | $9.9 |

| Teach for Texas Loan Repayment Assistance Program | $1.3 | $1.3 | $1.3 |

| Physician Education Loan Repayment Program | $12.6 | $15.3 | $14.9 |

| Texas Armed Services Scholarship | $1.3 | $3.4 | $3.4 |

| Math and Science Scholar’s Loan Repayment Program | $1.2 | $1.2 | $1.2 |

Sources: Legislative Budget Board, State Budget by Program “86th Regular Session, Final Bill” (http://sbp.lbb.state.tx.us/).

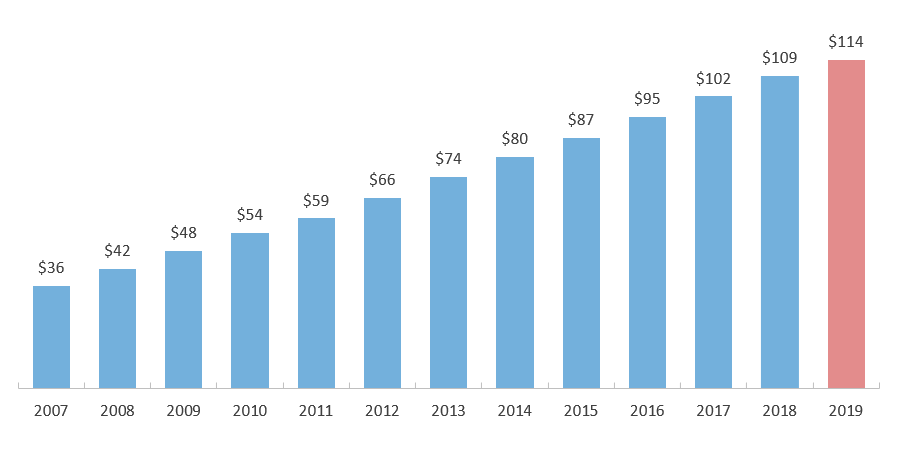

Estimated Outanding Student Debt in Texas

(in billions*)

While the growth rate of Texas student loan debt exceeds the overall U.S. growth rate, both rates have slowed somewhat in recent years. Texas has added about $7 billion per year in outstanding student loan debt since 2012, resulting in higher absolute growth but lower percentage growth than in previous years. For the U.S., absolute debt growth of about $75 billion annually since FY 2014 (and only $50 billion from 2018 to 2019) has been smaller than usual, such that the annual percentage growth has declined even more quickly.

At the state and national level, the majority of the outstanding student loan debt comes from federal loans, including Federal Family Education Loans (FFEL)**, Federal Direct Loans, and Federal Perkins Loans. Private and state-level education loans, which generally do not provide accommodations like income-linked repayment plans, deferments, or forgiveness, accounted for about 12 percent of student loans borrowed in AY 2018-19.

*Estimates are based on state-level per capita student debt averages from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel, which excludes persons without credit reports and persons living in counties where fewer than 10,000 people have credit reports. The result for a given year is adjusted by the same factor by which the result of this methodology for the United States as a whole deviates from the United States total outstanding student debt for that year as reported in the Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit. This adjustment, which was not made in some previous editions of SOSA, has been applied to all years.

**The FFEL Program ended in 2010, but borrowers are still making payments on outstanding FFEL balances.

Sources: U.S. Student Loan Debt Estimate: Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2019:Q4 (https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc/background.html), Texas Student Loan Debt Estimate: FRBNY Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, Q4 2007 through Q4 2018, and Household Debt and Credit Statistics by State (https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/databank.html); Non-federal borrowing: College Board. Trends in Student Aid 2019 (https://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/total-federal-and-nonfederal-loans-over-time).

Although the average loan balance continues to climb, the relationship between this trend and default rates is not straightforward. In fact, borrowers who are current on their loans tend to have higher balances, while those in delinquency or default tend to have lower balances. This counterintuitive pattern has one key cause: Borrowers incur higher debts by staying in school longer.

National Average Loan Balance by Loan Status for Federal Direct Loans

(Current dollars; as of Q1 2020)

The common explanation for the inverse relationship between borrowing and default is that persisting to graduation requires more borrowing but also leads to higher incomes, such that the loan payments are actually more affordable. Data support this explanation, but it is incomplete. Provisions like deferments and income-driven repayment plans offer borrowers effective means to avoid defaulting on federal student loans regardless of income. Helping borrowers acquire the knowledge and skills to navigate the repayment process early on can be an effective default prevention strategy for all borrowers, especially those more likely to drop out and be at greatest risk of default.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, Student Aid Data, Federal Student Loan Portfolio, “Direct Loan Portfolio by Delinquency Status (DL, ED-Held FFEL, ED-Owned)” (https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/portfolio); Cohort default rate: U.S. Department of Education, “Official Cohort Default Rates for Schools”, (http://www2.ed.gov/offices/OSFAP/defaultmanagement/cdr.html); Lifetime default projection: U.S. Office of Management and Budget, FY 2017 Budget for Dept of Education, (https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2017/assets/edu.pdf); 12-year default study: Woo, J. et al (2017). Repayment of Student Loans as of 2015 Among 1995-96 and 2003-04 First-Time Beginning Students. NCES. (https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018410.pdf).

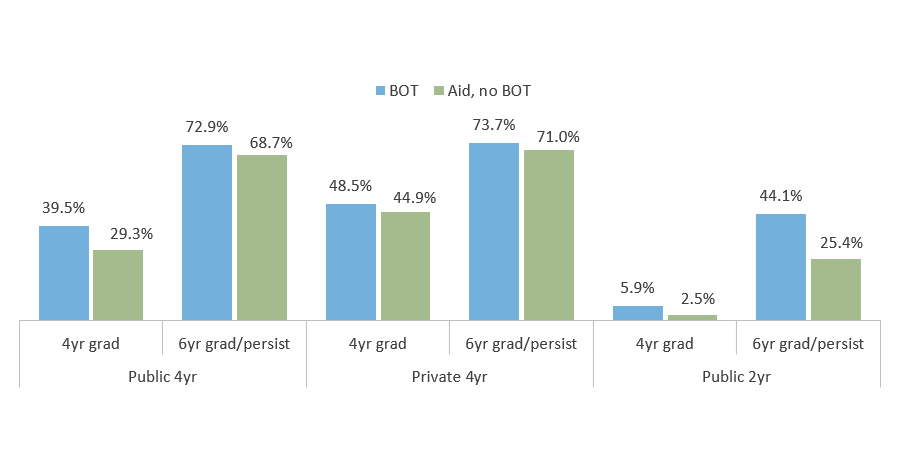

Students who received BOT loans consistently graduated at higher rates than students who received aid but no BOT loan. About forty percent of public university students with BOT loans graduated in four years, compared to 29 percent for non-BOT aid recipients. According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB), “these data suggest that the prospect of loan forgiveness may have been a strong enough incentive to influence behavior leading to more timely graduation”.

Graduation and Persistence Rates of BOT Recipients and Non-Recipients who Received Other Aid, by Sector (program lifetime)

Despite its promise, the BOT program was underutilized. Thirty-six percent of funds were not allocated in FY 2011, and only five out of 136 institutions disbursed their entire allocation. Four-year private institutions used 90 percent of their funds, while public universities used 64 percent. Community colleges used only 3 percent of their allocation.

In 2013, the Sunset Advisory Commission identified several issues hindering the BOT program. These included both poor structural fit and inadequate funding at community colleges, strict eligibility requirements, complexity, and lack of awareness. Federal “preferred lender list” rules likely contributed to this lack of awareness. Created to prevent conflicts of interest with private student lending, the rules prevent college staff from volunteering information about non-federal loans unless the institution develops a “preferred lender list”. This process entails risks to the institution and diverts scarce administrative resources. Public institutions, whose lower costs are less likely to require non-federal borrowing, are less likely to have preferred lender lists; this may partially explain their low utilization rates relative to private institutions. Acknowledging this issue, the Commission concluded that, “despite its flaws, the state benefits from a program [BOT] that supports access to college through no-interest loans and encourages graduation.” The Commission made several recommendations to improve the program, but the state opted to phase it out.

Sources: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB), Report on student financial aid in Texas higher education for fiscal year 2015, September 2016 (http://www.thecb.state.tx.us/reports/PDF/8504); Utilization: Sunset Advisory Commission, Staff report with hearing material: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, July 2013, pp. 48 (https://www.sunset.texas.gov/public/uploads/).

Borrowers who pursue PSLF take a risk. PSLF applies only to borrowers who enroll in IDR plans, which lower monthly payments but extend the payment period, resulting in higher interest costs over time. Borrowers who spend several years in IDR making qualifying payments can still lose eligibility due to employment changes, income growth, or Congressional action altering the PSLF terms; these borrowers now may face higher costs than if they had attempted to repay on the Standard Repayment Plan. Borrowers may also choose to pursue forgiveness through payment caps on certain IDR plans, though these options take longer and are also subject to Congressional action, and the Internal Revenue Service may tax this forgiveness as income (amounts forgiven under PSLF are not taxed).

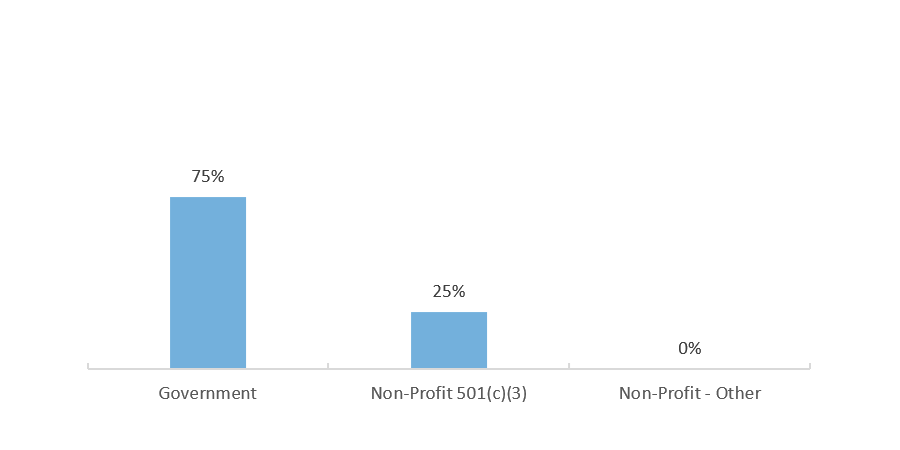

Approved PSLF Applications by Employer Type

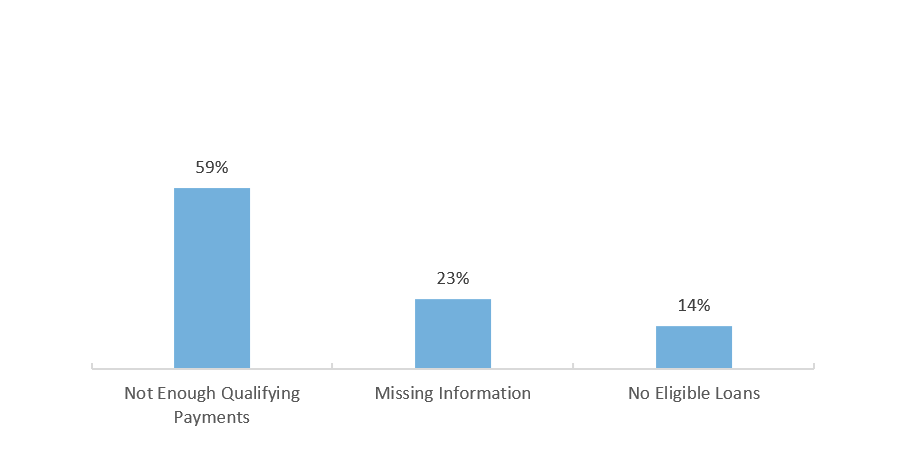

As of February 2020, 75 percent of the 2,828 approved PSLF applications were for government employees while the other 25 percent were for 501(c)(3) non-profit employees. Among the 163,576 applications deemed ineligible, 59 percent were rejected because the borrower had not made enough qualifying payments, 23 percent of the applications were missing information, and 14 percent applied for forgiveness on a loan that was not eligible.

Most Common Reasons for Ineligible PSLF Applications

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, Public Service Loan Forgiveness Data: https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/loan-forgiveness/pslf-data; U.S. House Committee of Education and the Workforce, PROSPER Act: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4508.

Ninety percent of higher education funding ($12.5 billion) will be allocated to institutions based on the following breakdown: 75 percent on the enrollment of full-time equivalent Pell Grant recipients and 25 percent on the enrollment of full-time equivalent students who don’t receive Pell Grants (online-only students were excluded for the purposes of determining this breakdown). The other ten percent will be allocated under different specified titles of the Higher Education Act as a way to defray expenses for the institutions and for grants to students.

Additionally, the CARES Act allows student loan borrowers whose loans were held by the U.S. Department of Education to take a six-month break from making payments. Interest will be waived during that time period and loan collectors will be prevented from garnishing wages, tax returns, and Social Security benefits to collect overdue payments.

These descriptions of the CARES Act were written on March 31, 2020. As the country works its way through the pandemic, there will likely be other legislation and regulation that impacts higher education institutions and its students.

Sources: CARES Act Text of Bill (https://www.nasfaa.org/uploads/documents/CARES_Act_Final_Text.pdf); Student Loan Payment Delay: MarketWatch.com, “$2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package lets some student-loan borrowers delay payments for six months” (https://www.marketwatch.com/story/2-trillion-coronavirus-stimulus-bill-gives-student-loan-borrowers-six-months-of-relief-2020-03-26).

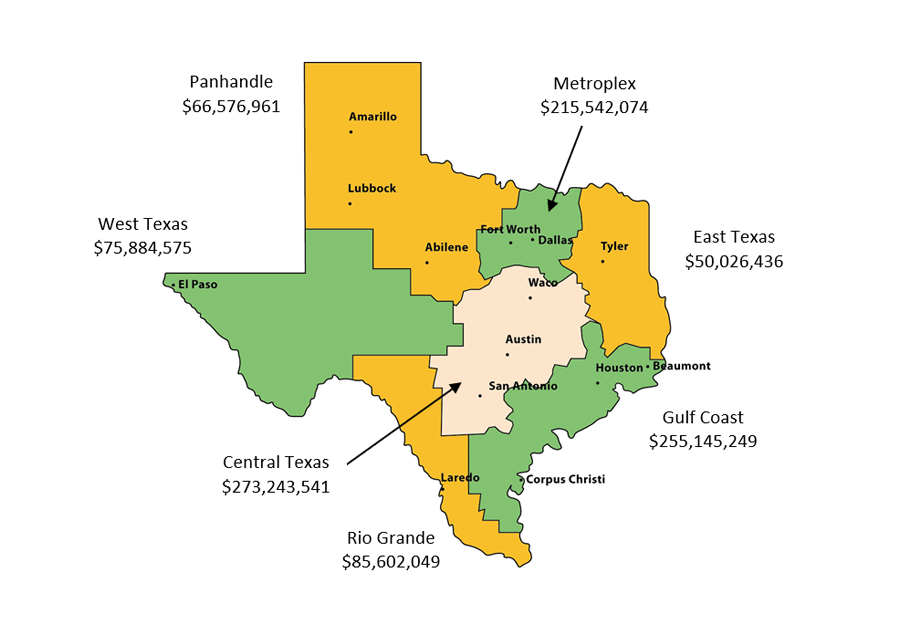

CARES Act Allocations at Texas Institutions by Region

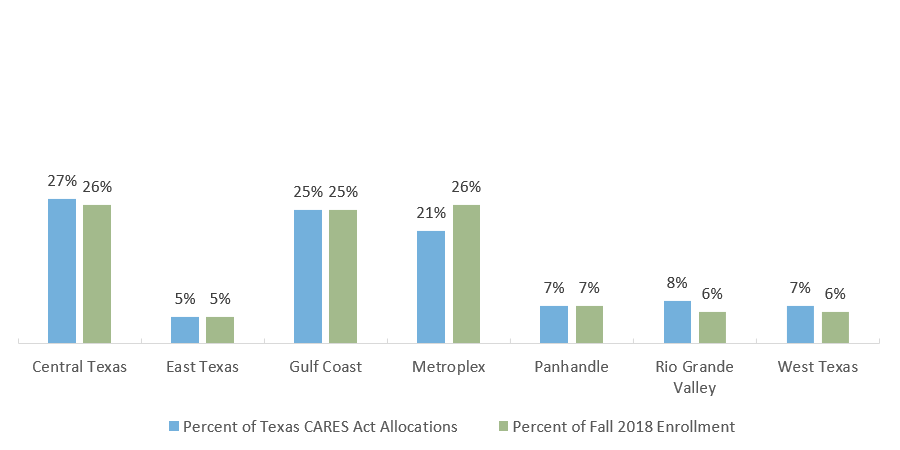

Two hundred ninety-six Texas institutions were allocated $1.02 billion through the CARES Act. The proportion of allocations by region are very similar to the proportion of Fall 2018 enrollment by region. Institutions in the most heavily populated regions of the state – the Central Texas, Gulf Coast, and Metroplex regions – will receive nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars in total to help students, employees, and higher education institutions weather the COVID-19 pandemic.

CARES Act Allocations at Texas Institutions by Region

Sources: U.S. Department of Education, Allocations for Section 18004(a)(1) of the CARES Act (https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/allocationsforsection18004a1ofcaresact.pdf); Enrollment by Region: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS Data (http://www.nces.ed.gov/ipeds/).

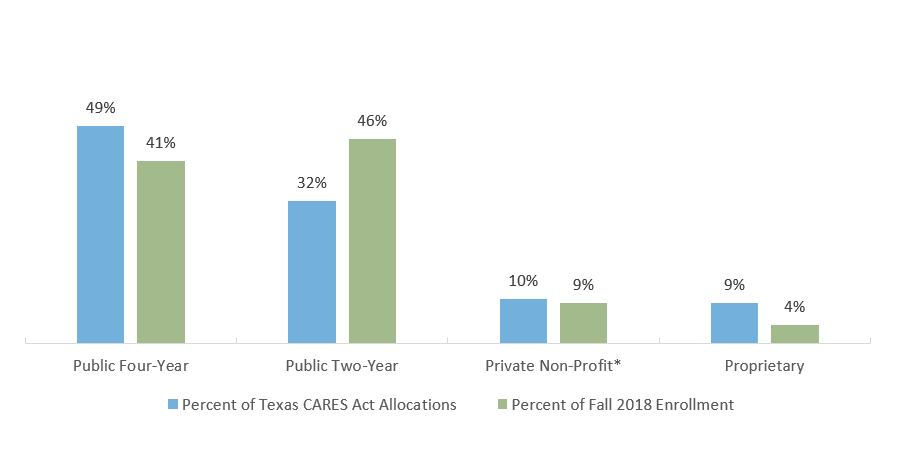

CARES Act Allocations at Texas Institutions by Sector

| School Type | Total Allocations | Number of Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Public Four-Year | $500,029,127 | 43 |

| Private Non-Profit* | $105,694,744 | 68 |

| Pubic Two-Year | $328,113,876 | 64 |

| Proprietary | $88,183,138 | 121 |

In March 2020, the CARES Act was signed into law to provide financial relief to people and organizations across the country while the COVID-19 pandemic stalled the economy. The bill included a provision to provide about $14 billion to higher education institutions and students. Using the guidance provided in the bill, the U.S. Department of Education developed a formula to determine how much funding each institution will receive. Texas institutions are allocated about $1.02 billion.

Compared to total enrollment figures, public two-year institutions are receiving proportionally less of the allocations while the other three sectors are receiving proportionally more. However, the CARES Act allocations are based on full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment, which is a calculation that determines how many students would be attending if all enrolled students were enrolled full time. The higher an institution’s proportion of part-time enrolled students, the lower their FTE enrollment number will be. Public two-year institutions in Texas have much higher proportions of part-time students than other sectors – 72 percent at public two-year, 30 percent at public four-year, 12 percent at private non-profit, and 14 percent at proprietary. The allocation formula also excludes students who were already exclusively enrolled in distance education. The public two-year sector in Texas has a higher proportion of distance education students compared to the other three sectors.

*This category includes 4-year or above, 2-year, and less-than 2-year institutions. Ninety percent of the Private Non-Profit Texas institutions receiving allocations are 4-year or above.