State of Student Aid in Texas – 2018

Section 4: Cost of Education and Sources of Aid in Texas

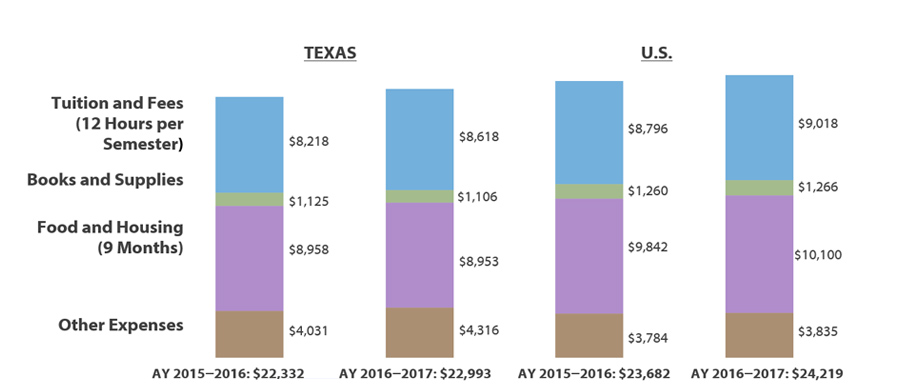

Weighted Average Public Four-year University Cost of Attendance for Two Semesters for Full-time Undergraduates Living Off Campus in Texas and the U.S. (AY 2015–2016 and AY 2016–2017)

The tuition and fees charged to students, along with living expenses, books and supplies, transportation, and other expenses, constitute a school’s cost of attendance. From 2016 to 2017, total costs increased by $661 in Texas and $537 nationally. Weighted for enrollment,* two semesters of full-time** undergraduate education at a Texas public four-year university averaged $22,993 in Award Year (AY) 2016–2017. This amount was $1,226 less than the national average. Total expenses in Texas have been below the national average for many years. With the exception of the “other expenses” category, all types of costs in Texas are lower than their corresponding national averages. The primary expenses facing students are not tuition and fees but food and housing, which make up nearly 40 percent of the cost of attendance. These costs are not discretionary: students must eat, and unless they live with parents — and 68 percent of U.S. public university undergraduates do not — they must pay rent. Together, food, housing, and other expenses comprise about 58 percent of the student budget, while tuition and fees make up 37 percent.

Cost of attendance is the starting point for determining financial aid. From the cost of attendance, the student’s expected family contribution (EFC)*** is subtracted to calculate the student’s financial need. Once financial need is determined, an aid package, consisting primarily of grants and loans, can be developed. What students actually pay for college depends on a number of factors, including the aid they receive and how frugally they live, as well as their enrollment patterns. To cut costs, many students enroll part time, work long hours, or both — but these strategies may increase their chance of dropping out of school without completing their program of study.

* An institution’s costs are multiplied by its enrollment. The sum of costs for all schools is then divided by full-time, undergraduate enrollment, such that schools with higher enrollments are given greater weight. See glossary for clarification.

** 12 semester hours or more.

*** EFC is determined through a federal formula that considers family income and size as well as the number of children in college, among other factors. The average amount that families actually contribute to educational expenses is unknown. In AY 2011–2012, 22 percent of dependent undergraduates enrolled at public four-year universities nationwide reported that they received no help from their parents in paying tuition and fees.

Sources: All Costs and Enrollments for 2016–2017: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2016 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All Costs and Enrollments for 2015–2016: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2015 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All other: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) 2012 (http://www.nces.ed.gov/das).

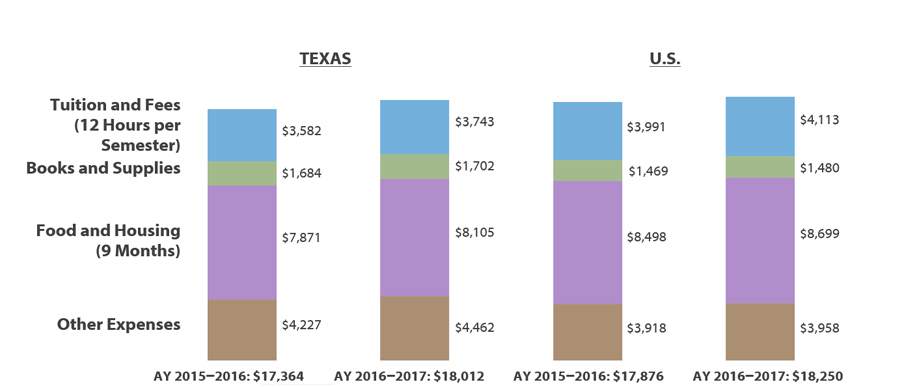

Weighted Average Public Two-year College Cost of Attendance for Two Semesters for Full-time Undergraduates Living Off Campus in Texas and the U.S. (AY 2015–2016 and AY 2016–2017)

Fifty-two percent of all Texas postsecondary students were enrolled in public two-year colleges in Award Year (AY) 2015-2016. The cost for two full-time* semesters at Texas public two-year colleges, weighted for enrollment,** averaged $18,012 in AY 2016–2017. This is an increase of $648 over the Texas average in AY 2015–2016 and is $238 less than the AY 2016–2017 national average. Costs in all categories have increased in Texas and nationally since AY 2014–2015, with the largest increases occurring in the other expenses and the food and housing categories in Texas.

The total cost of attendance for a student includes tuition and fees, books and supplies, and living expenses. The student’s financial need is calculated by subtracting the expected family contribution (EFC)*** from the cost of attendance, which is the basis for determining the financial aid package. This package consists primarily of grants and loans. The actual amount that students pay for college depends upon factors such as how much and what type of aid they receive, how frugally they live, and the number of credit hours they take. To save money, students may enroll in school part time, work long hours, or both — but these strategies may increase their chance of dropping out of school without completing their program of study.

* 12 semester hours or more.

** An institution’s costs are multiplied by its enrollment. The sum of costs for all schools is then divided by full-time, undergraduate enrollment, such that schools with higher enrollments are given greater weight. See glossary for clarification.

*** EFC is determined through a federal formula that considers family income and size as well as the number of children in college, among other factors. The average amount that families actually contribute to educational expenses is unknown. In AY 2011–2012, 31 percent of dependent undergraduates enrolled in public two-year colleges nationwide reported that they received no help from their parents in paying tuition and fees.

Sources: All Costs and Enrollments for 2016–2017: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2016 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All Costs and Enrollments for 2015–2016: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2015 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All other: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) 2012 (http://www.nces.ed.gov/das).

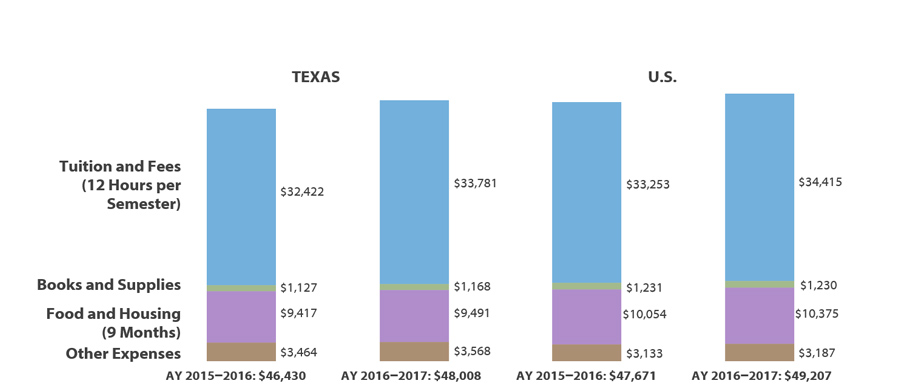

Weighted Average Private Four-year University Cost of Attendance for Two Semesters for Full-time Undergraduates Living Off Campus in Texas and the U.S. (AY 2015–2016 and AY 2016–2017)

The increase from Award Year (AY) 2015–2016 to AY 2016–2017 of the average cost of attendance at private four-year universities in Texas, at $1,578, was due almost entirely to an average $1,359 increase in tuition and fees. Weighted for enrollment,* the total cost of attendance for undergraduates at Texas private four-year universities for two full-time** semesters averaged $48,008 in AY 2016–2017. This is lower than the national cost of attendance for the same year, at $49,207. The difference is mainly because tuition and fees in Texas are $634 lower than the national average and food and housing costs in Texas are $884 lower than the national average. Approximately eight percent of students in higher education in Texas in AY 2015–2016 enrolled in private four-year universities, versus 40 percent who enrolled in public four-year universities.

As with public institutions, students who enroll in private four-year universities may receive an aid package, which primarily consists of grants and loans. A student’s need is calculated by subtracting the expected family contribution (EFC)*** from the cost of attendance in order to determine what kind of financial aid package they should receive. The total cost of attendance includes tuition and fees, books and supplies, and living expenses. To save money, students may choose to enroll in school part time, work long hours, or both — but these strategies may increase their chance of dropping out of school without a degree.

* An institution’s costs are multiplied by its enrollment. The sum of costs for all schools is then divided by full-time, undergraduate enrollment, such that schools with higher enrollments are given greater weight. See glossary for clarification.

** 12 semester hours or more.

*** EFC is determined through a federal formula that considers family income and size as well as the number of children in college, among other factors. The average amount that families actually contribute to educational expenses is unknown. In AY 2011–2012, 15 percent of dependent undergraduates enrolled at private four-year universities nationwide reported that they received no help from their parents in paying tuition and fees.

Sources: All Costs and Enrollments for 2016–2017: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2016 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All Costs and Enrollments for 2015–2016: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2015 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All other: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) 2012 (http://www.nces.ed.gov/das).

Change in Costs for Students Living Off Campus: Dollar and Percentage Change

(AY 2015–2016 to AY 2016–2017, Costs Weighted for Enrollment*)

| Texas | Public Four-Year | Public Two-Year | Private Four-Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ | % | $ | % | $ | % | |

| Tuition and Fees (12 Hours / Semester) | $400 | 5% | $161 | 4% | $1,359 | 4% |

| Books and Supplies | -$19 | -2% | $18 | 1% | $41 | 4% |

| Food and Housing | -$5 | 0% | $234 | 3% | $74 | 1% |

| Other | $285 | 7% | $235 | 6% | $104 | 3% |

| Total Change | $661 | 3% | $648 | 4% | $1,578 | 3% |

| U.S. | Public Four-Year | Public Two-Year | Private Four-Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ | % | $ | % | $ | % | |

| Tuition and Fees (12 Hours / Semester) | $222 | 3% | $122 | 3% | $1,162 | 3% |

| Books and Supplies | $6 | 0% | $11 | 1% | -$1 | 0% |

| Food and Housing | $258 | 3% | $201 | 2% | $321 | 3% |

| Other | $51 | 1% | $40 | 1% | $54 | 2% |

| Total Change | $537 | 2% | $374 | 2% | $1,536 | 3% |

Weighted for enrollment,* the total cost of attendance in all sectors in Texas and nationally increased between two and four percent between Award Year (AY) 2015–2016 and AY 2016–2017. By percentage, Texas had roughly equivalent or larger increases in all sectors compared to the nation.

The cost of attendance is the starting point for determining financial aid. What students actually pay for college depends on a number of factors, including the aid they receive and how frugally they live, as well as their enrollment and work patterns. To cut costs, many students enroll part time, work long hours, or both. In AY 2011–2012, 62 percent of all undergraduates nationwide attended less than full time/full year — that is, they either took fewer than 12 hours per semester or did not attend at least two semesters — and 66 percent worked while enrolled (27 percent of which worked full time**). Full-time work and part-time enrollment are associated with each other and also with lower completion rates: 79 percent of U.S. undergraduates who work full time while enrolled attend less than full time/full year, slowing their academic progress.

* An institution’s costs are multiplied by its enrollment. The sum of costs for all schools is then divided by full-time, undergraduate enrollment, such that schools with higher enrollments are given greater weight. See glossary for clarification.

** 35 or more hours per week; includes work-study/assistantship.

Sources: All Costs and Enrollments for 2016–2017: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2016 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All Costs and Enrollments for 2015–2016: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2015 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); All other: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) 2012 (http://www.nces.ed.gov/das).

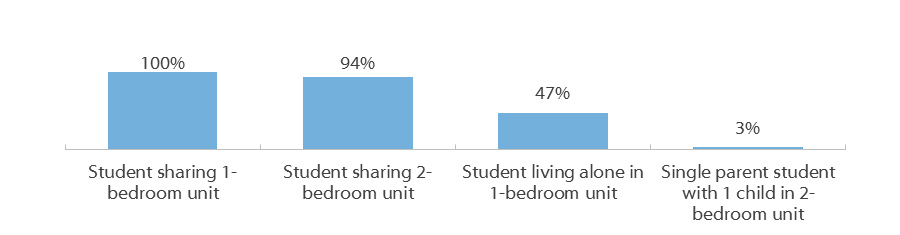

Percentage of Texas Public Universities Where the Institution’s Room and Board Estimate Covers the USDA/HUD Food and Housing Cost Estimate, by Living Situation (AY 2016–2017)

Food and housing make up nearly 40 percent of the cost of attending a public university in Texas. These costs are variable, but they are not discretionary. Students have some control over their lifestyle choice, but they must eat and pay rent. As the food and housing cost estimate is the largest single component of the official cost of attendance at both community colleges and public universities, it has critical implications for the types and amounts of financial aid that students are offered and the amounts institutions expect that students/families can afford to pay.

Using their knowledge of housing located in areas popular with students, Texas universities attempt to estimate the cost of food and housing that is modest but adequate. For the 2016–2017 Award Year (AY), this average estimate is $8,830,* or $981 per month. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates the minimum dietary needs of an adult can be met on $268 per month provided that all food is prepared at home, an unlikely scenario for young adults. Subtracting $268 from $981 leaves $713 for rent and utilities. The addition of one small pepperoni pizza per week, however, would raise the monthly food budget to $310,** leaving $671 for rent and utilities.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates the average nine-month cost of rent and utilities for a one-bedroom unit in the counties and Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs)*** where Texas public universities are located to be $6,731, or $748 per month. Sharing housing lowers the cost: a shared one-bedroom costs $374 per person and a shared two-bedroom costs $464.

These data suggest that a thrifty student who is a savvy grocery buyer, cooks nearly all his meals, and shares housing should manage to stay within the institutional room and board estimate of $981 per month. However, a student who shares all these traits and lives alone will probably not be able to stay within the estimate at about half of Texas universities. At 97 percent of Texas universities, the room and board estimate is too low for a single parent with a dependent. About 28 percent of U.S. undergraduates in AY 2011–2012 had dependent children, and about 15 percent were single parents.

Average USDA/HUD Food and Housing Costs for Two Semesters (9 Months) for Counties and MSAs*** Where Texas Public Universities Are Located (AY 2016–2017)

| Student sharing 1-bedroom unit | Student sharing 2-bedroom unit | Student living alone in 1-bedroom unit | Single parent student with 1 child in 2-bedroom unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | $2,408 | $2,408 | $2,408 | $3,614 |

| Housing | $3,366 | $4,179 | $6,731 | $8,358 |

| Total | $5,774 | $6,587 | $9,139 | $11,972 |

*$8,953 when weighted for enrollment; see glossary for clarification. ** Based on the cost at Conan’s Pizza near the University of Texas at Austin, February 2018. *** A Metropolitan Statistical Area is a geographic area of 50,000 or more inhabitants.

Source: All Costs and Enrollments for 2016–2017: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2016 (http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/); U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, June 2017.” (http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/USDAFoodCost-Home.htm); U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). “Fair Market Rents 2017 for Existing Housing, October 2017,” (http://www.huduser.org/datasets/fmr.html); All other: U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) 2012 (http://www.nces.ed.gov/das).

Institutional Living Cost Allowance vs. County Cost of Living Estimate

| Sector | Institutions # |

Above Estimate by $3,000+ % |

Within $3,000 of Estimate % |

Below Estimate by $3,000+ % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-year or above | 2,538 | 8.3 | 60.9 | 30.8 |

| Public | 634 | 9.5 | 71.6 | 18.9 |

| Private not-for-profit | 1,200 | 7.8 | 55.4 | 36.8 |

| Private for-profit | 704 | 8.1 | 60.6 | 31.3 |

| 2-year | 2,107 | 10.1 | 60.4 | 29.5 |

| Public | 1,019 | 7.7 | 63.2 | 29.1 |

| Private not-for-profit | 126 | 15.9 | 53.1 | 31.0 |

| Private for-profit | 962 | 11.9 | 58.5 | 29.6 |

| Less-than-2-year | 1,797 | 15.1 | 45.3 | 39.6 |

| Public | 228 | 14.0 | 40.8 | 45.2 |

| Private not-for-profit | 66 | 4.5 | 48.5 | 47.0 |

| Private for-profit | 1,503 | 15.8 | 45.8 | 38.4 |

| Grand Total | 6,442 | 10.8 | 56.4 | 32.8 |

The federal definition of the cost of attendance (COA) includes tuition, fees, room and board (food, housing, transportation, and other miscellaneous costs of living), books, and supplies. The COA is important because it is part of the equation that helps determine how much financial aid students are eligible to receive in grants and loans from federal, state, and institutional sources. Federal law requires each institution to “determine an appropriate and reasonable amount” using its own method. Typically, institutions recalculate their COA annually. For direct educational costs, this is a relatively straightforward process. Determining living costs can be somewhat more complicated.

In keeping with federal law and the principal of local control, there is no regulation or standardized system for determining COA, including the living cost components. Schools use various methods to research and estimate these costs, including student surveys, interviews, and economic data. Organizations such as the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators and the College Board provide some guidance, but each institution has the flexibility and responsibility to reach its own estimate by its own means.

Sources: Wisconsin HOPE Lab, The Costs of College Attendance: Trends, Variation, and Accuracy in Institutional Living Cost Allowances, by Robert Kelchen, Braden J. Hosch, and Sara Goldrick-Rab (2014) (http://www.wihopelab.com/publications/Kelchen%20Hosch%20Goldrick-Rab%202014.pdf

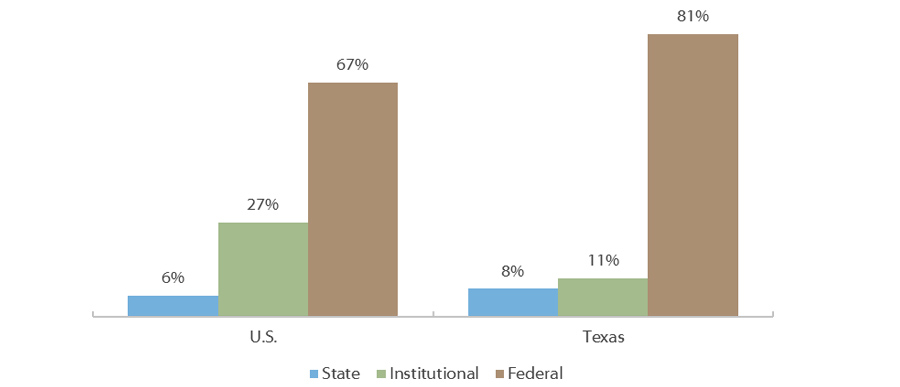

Direct Student Aid by Source (AY 2015-2016*)

College students receive financial aid mainly from three major sources: the federal government, the state government, and the colleges and universities they attend (“institutional” aid). Of these three, the federal government’s contribution is by far the largest for most students. Nationally, the federal government provided 67 percent of the generally available direct financial aid* for undergraduate and graduate students in Award Year (AY) 2015–2016. In Texas, the federal government’s role is much larger, accounting for 81 percent of aid.

The Texas state government and state governments on average across the U.S. provided a similar percentage of the available aid to students in AY 2015–2016**, at eight percent and six percent respectively.

Texas colleges and universities, through institutional grants,*** provided a much smaller percentage of financial aid than colleges in other states. Texas institutions provided 11 percent of aid versus 27 percent for colleges nationally. This may be in part because relatively few students in Texas attend private institutions, which often charge high sticker prices but use much of the revenue to give large grants and scholarships to many students based on financial need, academic merit, and other factors.

* Direct student aid includes aid that is generally available, goes directly to students, and derives from state and federal appropriations, plus institutional grants. All aid shown in graphs is for AY 2015–2016, except the private institutional aid in the Texas graph, which is for AY 2011–2012.

**The State of Texas, like other state governments, also supports public institutions through direct appropriations and tuition waivers.

*** Includes the Texas Public Educational Grant (TPEG) for AY 2015–2016 as well as private institutional aid reported to the Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT) for AY 2011–2012.

Source: Private institutional aid: Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT) “Annual Statistical Report 2013”, (https://www.icut.org/communications/publications/); State aid and TPEG: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “2015–16 Financial Aid Database,” Austin, Texas, (unpublished tables); Federal aid in Texas: U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid Data Center (https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/data-center); Aid in the U.S.: The College Board. Trends in Student Aid 2017 (http://trends.collegeboard.org/).

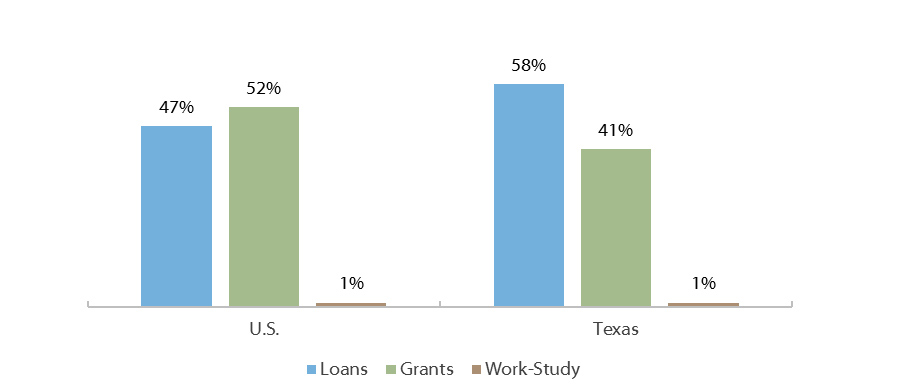

Direct* Student Aid by Type (AY 2015-2016)

Compared to national averages, Texas college students have relied and continue to rely even more heavily on loans. In AY 2015–2016, 58 percent of aid in Texas came from loans and 41 percent came from grants, including state and institutional grants.* Nationally, 47 percent of aid was in the form of loans and 52 percent came from grants. Most student loans in Texas and nationwide are Federal Direct loans.

One percent of student aid in Texas and nationally comes from work-study dollars. The Federal Work-Study Program provides part-time jobs to students with financial need. Whether on campus or off campus, the program encourages employment related to the student’s course of study whenever possible.

* Direct student aid includes aid that is generally available, goes directly to students, and derives from state and federal appropriations (including both FFELP and FDLP loans), plus institutional grants. All aid shown is for AY 2015–2016, except the private institutional aid in the Texas graph is for AY 2011–2012.

Source: Private institutional aid: Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT) “Annual Statistical Report 2013”, (https://www.icut.org/communications/publications/); State aid and TPEG: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, “2015–16 Financial Aid Database,” Austin, Texas, (unpublished tables); Federal aid in Texas: U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid Data Center (https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/data-center); Aid in the U.S.: The College Board. Trends in Student Aid 2017 (http://trends.collegeboard.org/).

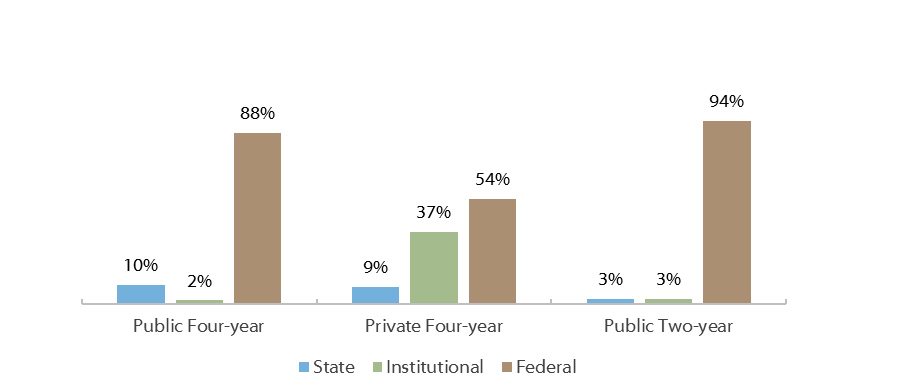

Direct Student Aid by Source in Texas, by Sector (AY 2015-2016*)

Students enrolled in the Texas public two-year sector are the most dependent on the federal government for their financial aid, followed closely by students in the public four-year sector. Students in the public four-year sector receive more state support, proportionally, than those in the two-year sector.

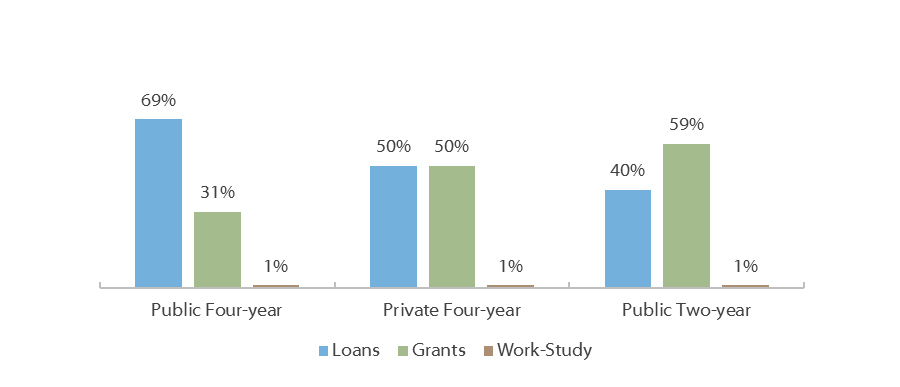

Direct Student Aid by Type in Texas, by Sector (AY 2015-2016*)

Direct student aid in the private four-year sector in Texas is split almost evenly between loans and grants. The student aid in the public two-year sector is more likely to be grants than loans (in large part because the federal Pell grant covers most if not all tuition/fee costs for many students), while the opposite is true for the public four-year sector. In all sectors, work-study aid encompasses less than one percent of total student aid.

* Direct student aid includes aid that is generally available, goes directly to students, and derives from state and federal appropriations (including both FFELP and FDLP loans), plus institutional grants. All aid shown is for AY 2015–2016, except the private institutional aid in the Texas graph is for AY 2011–2012. Comparable aid data for the private for-profit (proprietary) sector is unavailable.