Students who struggle with meeting basic needs like food, housing, and utilities are vulnerable to enrollment disruptions regardless of their academic ability or potential. Unfortunately, research is documenting an alarming number of students experiencing threats to their basic needs. Schools that address their students’ challenges with the indirect costs of college have seen improved student performance outcomes.

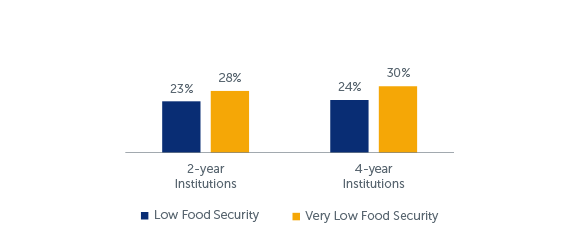

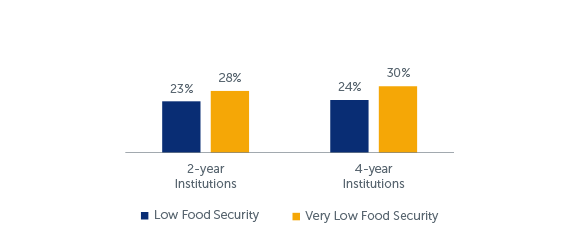

- Respondents at 2-year and 4-year institutions have similar levels of food insecurity. (Q77-82)

- More than half of respondents at 2-year and 4-year institutions showed signs of either low food security or very low food security.

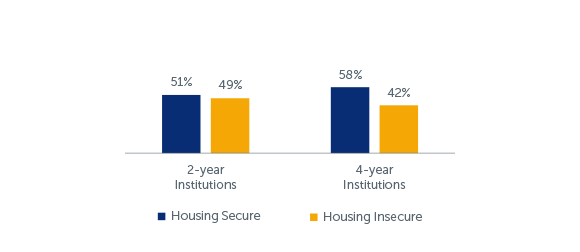

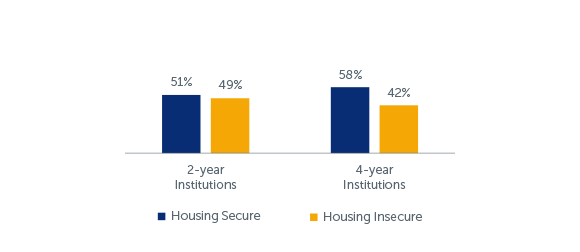

- Many students are struggling to maintain secure housing. (Q83-88)

- Nearly half of respondents at 2-year institutions (49 percent) – and 42 percent of respondents at 4-year institutions – showed signs of being housing insecure.

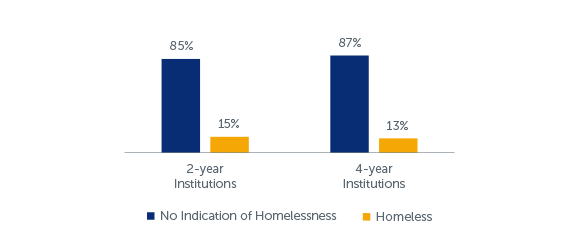

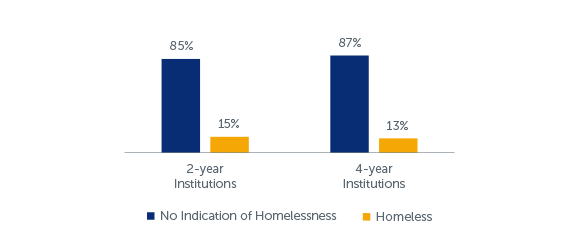

- Homelessness is an issue that affects a sizeable portion of college students. (Q89-98)

- A noteworthy percentage of respondents at 2-year (15 percent) and 4-year (13 percent) institutions report homelessness.

Q77-82: USDA Food Security Scale (30-Day)

More than half of respondents at 2-year and 4-year institutions showed signs of either low food security or very low food security. (Q77-82)

- At 2-year institutions, 23 percent of respondents show signs of low food security and 28 percent had very low food security.

- The pattern at 4-year institutions was similar to 2-year schools – 24 percent of respondents showed signs of low food security and 30 percent had very low food security.

- Students with low or very low food security responded at higher rates that they worry more about having enough money to pay for school (Q51) and at lower rates that they know how they will pay for next semester (Q52). They were also more likely to be first-generation students, more likely to be female, and more likely to report that they would have trouble getting $500 in cash or credit in case of an emergency (Q44). For more detail on the above findings, see Appendix C. Q77-82

Q83-88: Housing Security Scale

Many students struggle to maintain secure housing. See Appendix B to view response frequencies for every question used to calculate the housing security scale. (Q83-88)

- At 2-year institutions, nearly half of respondents showed signs of being housing insecure, compared with 42 percent of respondents at 4-year institutions.

- Respondents who were housing insecure answered at higher rates that they would have trouble getting $500 in cash or credit in case of an emergency (Q44). These respondents also responded at higher rates that they worry about having enough money to pay for school (Q51) and at lower rates that they know how they will pay for college next semester (Q52). In addition, respondents with housing insecurity were more likely to be first-generation students, female, enrolled part-time, and/or over 25 years of age. For more detail on the above findings, see Appendix C. Q83-88

Q89-98: Homelessness Scale

Homelessness presents serious obstacles to achieving full academic potential. See Appendix B to view response frequencies for every question used to calculate the homelessness scale. (Q89-98)

- Fifteen percent of respondents at 2-year institutions – and 13 percent at 4-year institutions – indicated homelessness since they started college or within the 12 months prior to the survey.

- Respondents who were homeless answered at higher rates that they would have trouble getting $500 in cash or credit in case of an emergency (Q44). They also responded at much higher rates that they worry about having enough money to pay for school (Q52) and at much lower rates that they know how they will pay for college next semester (Q53). For more detail on the above findings, see Appendix C. Q89-98

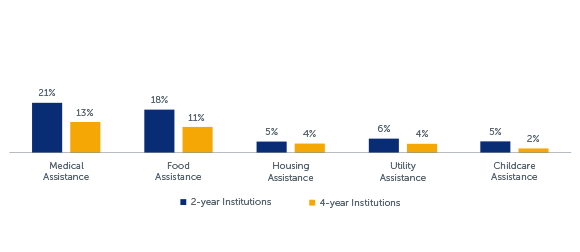

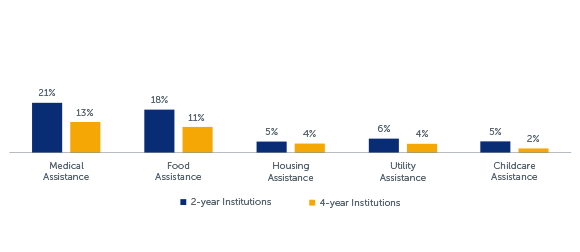

Q54-58: Percent of respondents who indicated use of public assistance, by assistance type

Connecting students with public assistance for which they may be eligible helps address the alarming levels of basic needs insecurity among college students. (Q54-58)

- At 2-year institutions, fewer than one in five respondents (18 percent) indicated using public food assistance, 21 percent used public medical assistance, and five percent used public housing assistance.

- Use of public assistance is somewhat lower at 4-year institutions where 11 percent of respondents indicated using public food assistance, 13 percent used public medical assistance, and four percent used public housing assistance.

- Unfortunately, eligibility rules for SNAP – the primary federal program for addressing hunger in America – excludes most college students unless they meet certain exceptions.16 Q54-58

Eligible low-income students face resource challenges that can be partially addressed through access to public benefits. Many campuses are connecting students to these public benefits, and some colleges even staff full-time social workers to support students facing resource scarcity.5

Institutions are building crisis support teams to case manage students experiencing difficulty securing basic needs. This model of case management has been successful in supporting students facing mental health crises on campuses for decades and is now being applied to students facing basic needs and financial crises.

Many institutions now provide emergency support services for students such as food pantries, temporary housing, and/or emergency funding. Access to these services are often housed in a central resource center to provide a single location for all students seeking support.17

Institutions are reconsidering their policies regarding student housing availability to ensure students who are housing insecure or homeless aren’t affected during holidays or breaks.18

Some campuses ensure a low-price and healthy food option at all campus dining areas. Some institutions work with cafeteria vendors to offer a basic meal at wholesale, rather than retail prices, while others provide food vouchers for certain students.21

Institutions are addressing housing insecurity and homelessness by partnering with local housing authorities to offer housing vouchers, working with community organizations to build housing, and advocating for state programs supporting these vulnerable students.5, 19, 20